Dune Ecology

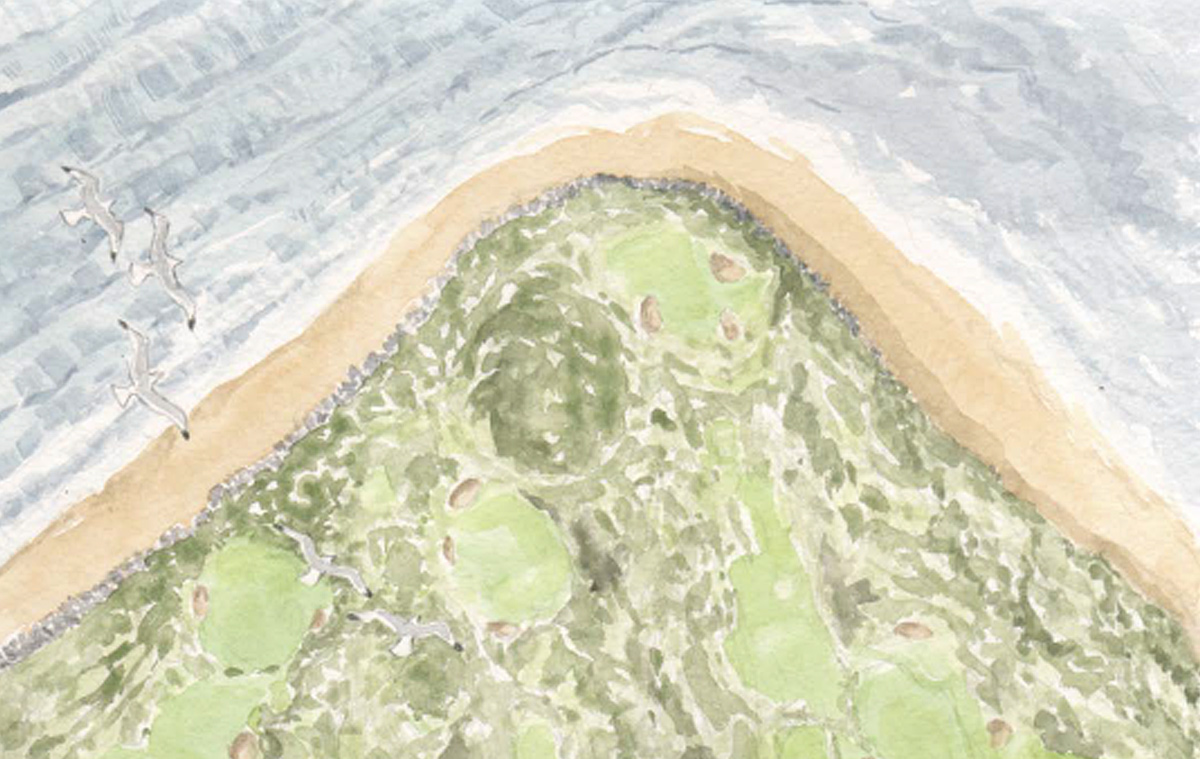

Most of our dune systems are recent in origin. They formed mainly between two and five thousand years ago when Ice Age sediments, exposed by lower sea levels, were blown inshore to accumulate behind beaches along our coasts. Often they develop at the outfall of rivers, such as the Inagh. Lahinch comes from the Irish meaning ‘half-island’ or peninsula, a fair description of the situation of the links. Dune systems are not stable: their attempts to advance towards the sea, thus forming new land, are constantly being undermined by the erosional action of the sea. Human intervention, in the form of coastal defences, is thus necessary to maintain a dune system intact.

Long-term stability depends on the establishment of natural vegetation such as marram grass, which by forming an intricate root-mat, holds the sand in place enabling other dune-plants to invade. In time a diverse suite of specialised plants becomes established, adapted to life on the lime-rich, well-drained (but drought-prone) sand. The diverse flora supports an equally diverse fauna of lime-loving ‘mini-beasts’ like insects and snails, open country birds such as larks and pipits and grazing animals like rabbits and hares.